Roman Warfare

To discuss Roman warfare, we must first consider the context of warfare more broadly in ancient times. In the ancient world food and supplies were not as easily sourced as the modern day, with our modern supply lines and industrial agriculture we can source food year-round without issue. However, due to the seasonal nature of food supply, as well as the difficulty of navigating terrain that often had no or minimal infrastructure in terms of roads or paths, warfare in the ancient world was essentially limited to the summer months. This meant that wars were planned with a season of campaigns in mind, accounting for distance and time spent travelling. While this seasonal aspect of war continues even into modern times, it was much more prohibitive on winter campaigns and warfare in the ancient world. Additionally, as most people worked in agriculture, growing their own food on farms at home, the need for males in the household to go to war was a detriment to the available manpower on farms and thereby food and personal income production. Overall, this created a need for most societies to balance the costs of engaging in war both in the short term economically and in terms of mortal consequences, versus the potential gains from war in the form of territory or spoils of war. These considerations were the main limiting aspect on warfare in the ancient world, where no universal and global rights or laws surrounding warfare were yet existant.

Rome as a society became much larger, and more administratively organised than its surrounding enemies over the centuries, especially compared to its northern neighbouring states such as the Gauls and Dacians. This allowed the Romans to organise and fund supply lines for large, professional armies at long distances, and is the partly the reason for one Roman claim to fame, the Roman roads. Additionally, with the increased scale of the Roman state, so too was the available manpower increased, allowing continual recruitment and warfare. A particularly notable example of this is when Rome suffered numerous catastrophic defeats during the Second Punic War against Carthage, after these defeats the Romans elected dictators and raised new legions quickly to replace their lost forces, almost being conquered by Hannibal. Although ancient historians recorded accounts of the various wars passed down to us through time, many of these accounts are fraught with possible inaccuracies or biases, which must be considered, especially in terms of records of numbers of troops at battles, deaths, casualties etc. However, some campaigns, especially those of Julius Caesar, are well recorded contemporaneous to the events and show us how a campaign could progress over time and space.

An Example Campaign (The Gallic War)

The Gallic War is one of the most well-documented conflicts in Roman history. This is largely due to Caesar's firsthand account, recorded in De Bello Gallico, otherwise known as The Gallic Wars. The 8-year-long campaign is visualised on the map below, with a timeline and supplemental information detailing the major events of the war. The dates for Caesar's campaign are based upon Chronological Tables for Caesar's Wars (58-45 BCE) by Ramsey, J. T. and Raaflaub, K. A. (2018).

Legend:

|

Romans

|

Roman Allies

|

Enemy Forces

Start of the Conflict

Jan. - Mar. 58 BCE

After gaining Imperium Julius Caesar remains near Rome for a short time to defend recently passed legislation from attacks by political oppenents. At the same time the Helvetii people who inhabited the Swiss plateau, seeking more land to live on and occupy, burn their homes and villages in preparation for a great migration south of the river Rhône towards Roman territory. Caesar marches his forces north towards Geneva to meet the threat of this incursion.

De Bello Gallico: 1.2-7

*All locations and dates are approximate/illustrative

- Drag the timeline above to explore different events of the Gallic War -

Reasons for War

The motivations for one state to come into conflict with another can be as varied as those which bring individuals into conflict. However, in the case of Rome a lot of the reasons for their conflicts can be broadly broken down into a few primary motivations. Namely these are conquest/expansion wars, defensive wars, putting down rebellions, and punitive wars.

Conquest wars are perhaps the most defining feature of the Romans in the modern mind. Rome often engaged in expansionist and territorial conflicts in an effort to stretch its empire further and bring more states under its control. It is through these wars that Rome first conquered its neighbours on the Italian peninsula, then in Greece, Asia Minor, North Africa, and Spain, then finally in Central Europe, Britain, Egypt, Asia, and Germany at its height (Fig. 01). This is the reason that Roman culture was spread all over the Mediterranean, through its language, religion, and art. This is also the reason that over the centuries Roman culture itself, and what it meant to be a Roman citizen changed dramatically, as Rome absored conquered nations and underwent a cultural and religious syncretism.

In defensive wars Rome would often seek to undergo a war of retribution and conquest after fighting off the enemy. This is what happened during the Second Punic War when the Carthaginian general Hannibal inflicted harsh defeats on the Romans before finally being defeated. After the war Rome demanded heavy payments from the subdued Carthaginians, and later instigated a Third Punic War on flimsy grounds in order to destroy the Carthaginian state for good. In this way the Third Punic War could be described as a punitive war, seeking to punish other states for perceived wrongdoing or slights. Rome was throughout many centuries also tasked with putting down rebellions in its subject provinces. Overwhelming force would usually make quick work of any rebels, and often a punitive war was waged against the local populace to discourage further uprisings.

One of the most important things to consider when discussing Roman motivations for war is that of political ambition. While it may seem unusual to the modern person, an elected officials (or the emperors) ability to wage war effectively was one of the most important qualities they could have. Under the Republican system the highest office was Consul, and consuls were the head of the Roman armies, with Legates serving underneath them. However, with a term of only one year, consuls had to make gains in the short timespan of their power, both for wealth and prestige which could confer further honours. This is one of the primary reasons why Rome's reputation for war is so prolific. It is a consequence of its political system that each consul elected each year felt the need to obtain victories, hence Rome was in a near constant state of war.

Logistics of War

Supply and its limitations was often the bottleneck on pursuing a war for all states throughout history. An army marches on its stomach, but even things like water, equipment and animals was a requirement in the ancient world, much like how modern armies require constant supplies of ammunition, vehicles, and medical supplies. In this regard the Romans were perhaps the best at this aspect of war during their own time. The Romans built roads in conquered provinces to ease travel, constructed a camp at the end of every day of marching, made soldiers carry a portion of their own supplies and equipment, and maintained a baggage train and local supply sources.

Discipline was an important part of the professionalism that made the Roman army so effective, with regular drills and training, as well as strict punishments for stepping out of line. This disciplined mindset extended to other logistical areas like marching, camp construction, and carrying supplies. Roman soldiers would often march dozens of miles a day when on campaign, requiring a high level of physical fitness. Additionally, a soldier would carry his own armour, shield, weapons, and some food and other equipment while marching, thereby adding to this difficulty. Soldiers also lived in groups of eight legionaries per tent, and this was known as a contubernium. Together the contubernium would march, sleep, cook, and eat together, building strong personal bonds in the process.

The amount of baggage carried by soldiers was not, alone, enough to supply the whole army for a campaign, and so the Roman army maintained a large baggage train consisting most often of mules to carry even more. Mules were faster than other animals, relatively easy to manage, and could travel across most terrain, making them the ideal animal for this task. Wherever possible the army would also set up local supply lines from allied settlements, or even extracting supplies from local people in enemy territories by force. Soldiers would also be tasked with foraging, both for food and water, as well as supplies of firewood for cooking. This could often be dangerous, with ancient accounts detailing soldiers being attacked by the enemy while foraging for food in hostile territory.

While the main equipment was obviously supplied at the recruitment stage of the legionaries before the outset of a campaign this did not mean that replacements were not needed. Weapons and armour could be damaged in battle, needing repairs or replacement while in the field. In later stages of the empire, due to the expansion of Roman settlements and craftsmen, new weapons could be sourced locally by the soldiers who were stationed at the forts and bases nearby. In many cases these craftsmen worked as part of the army inside these locations. Additionally, it is known that the army also had doctors, who would treat soldiers wounds and ailments with the medical knowledge of the time.

Battle & Sieges

Somewhat unsuprisingly, war is often viewed primarly through the scope or viewpoint of battles, however these events comprised an objectively small portion of any war. Most of the time on campaign would be spent marching, scouting, constructing camps, or on some occasions engaging in sieges. While sieges also involved combat they are defined seperately from battle itself, as often, much like battle, the combat portion was proportionally small compared to the preparation for the siege.

Battle itself was a tense, but almost ritual affair. It was common for armies to be within close proximity to one another for days and weeks before actually coming to combat. Parleys between generals, as well as indecisive cavalry skirmishes before a main battle were common. These allowed each army to build confidence over the enemy and test their enemy's mettle without the full commitment of the army. Entire armies would also sally out of their camps on several occasions and take up battle line formation and face each other, hurling insults and sometimes ranged weapons, with neither side coming to direct hand-to-hand combat. This would often be because one side had more favourable ground, being positioned on hill or other ground that offered an advantage, thereby discouraging the enemy from coming to blows. All of these aspects of battle emerged because open ground battles could be the decisive event of an entire war. If an army was destroyed in battle they would usually rout and disperse, and many soldiers were killed in the process. With the army dispersed the winning side could take control of the area with little resistance.

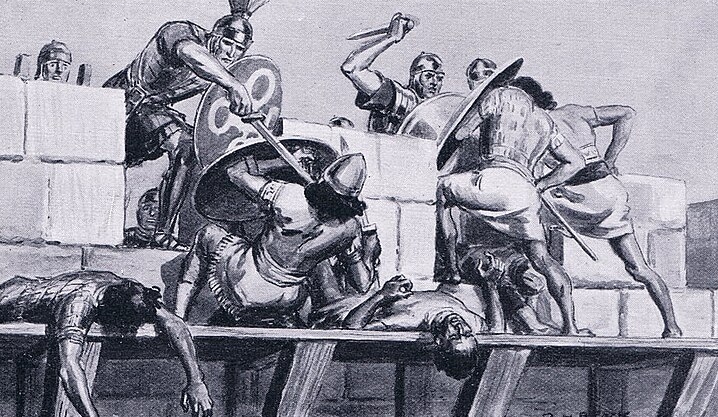

Sieges were a different story. If an enemy decided to hold up in a fortified settlement, city, or fort, the attacking party would be disadvantaged in any frontal assualt on the stronghold. For this reason the Romans became experts in engineering and constructing siege equipment. This included building large earthen ramps, siege towers, and battering rams; on other occasions they may have tunneled to collapse the enemy walls, or encircled entire settlements with ramparts and palisades in order to cut off enemy supplies and starve them out. Once the walls were breached it was common for the Romans to seek to do punitive damage to the enemy for the long siege, this might include looting the whole settlement, killing many of the civilians as well as the soldiers, or enslaving the entire populace of the city.